Sign up here |

|

|---|

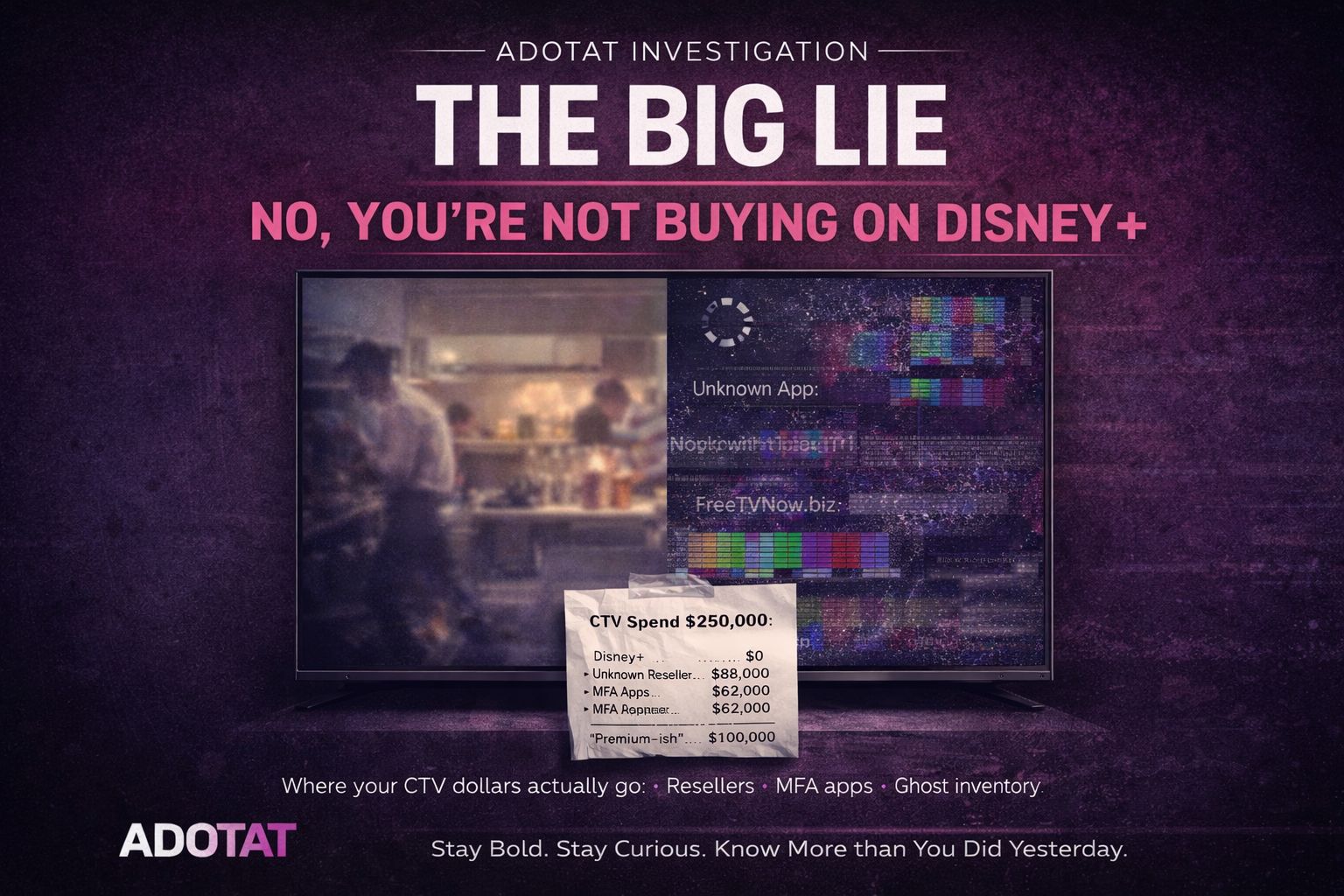

The Big Lie

No, You're Not Buying on Disney+

Adform put out a press release this week. Growing partnership with Disney+. Premium CTV inventory. Direct access. Scale.

You know the drill. Every DSP on the planet has made this exact announcement. They all have the Disney slide in the pitch deck. They all promise they can put you on Hulu, on ESPN, on the shows people actually watch. It's the load-bearing wall of every CTV sales pitch in the industry: we can get you premium, we can get you scale, we can get you Disney.

It's bullshit. Complete, structural, provable bullshit.

I don't mean that as an opinion. I mean it as a description of how the plumbing actually works. Most of what gets sold as "Disney" or "premium CTV" through open programmatic exchanges does not end up on Disney's flagship shows. In a lot of cases, it doesn't end up on Disney at all. And the people who can actually see where the money goes? They know it. They've known it for years.

Two Conversations I Was Not Looking For

I have to tell you how this story started, because the origin is half the point.

I was not reporting on CTV fraud. I was not pulling a thread. I was not on this beat. I was having two completely unrelated conversations, weeks apart, with two executives at CTV measurement companies. Both are founders. Both built their companies inside the guts of the system. Both are plugged into publisher clean rooms, DSP bid streams, verification pipelines. These are people who see the actual receipts, not the pitch deck version of where impressions land.

In both conversations, we were talking about something else entirely. And in both conversations, unprompted, they opened up. Not because I was digging. Because the conversation wandered into territory where they felt like being honest. That was the word both of them used. Independently. Honest. Like they'd been carrying around something heavy and decided, you know what, let me just put this down for a minute.

The first conversation went about forty minutes longer than it was supposed to. Three weeks later, the second one did the same thing. Different person. Different company. Different part of the measurement ecosystem.

Same exact claims. Same numbers. Same conclusions. Same frustration.

That is what scared me. Not the fraud itself. Fraud in ad tech is about as surprising as finding pigeons in New York. What scared me was the convergence. Two people who do not talk to each other, who work in different corners of the same system, arriving independently at identical conclusions about how broken CTV actually is. Not similar conclusions. Identical ones.

So I started pulling the thread. And the further I pulled, the worse it got.

What Disney Themselves Will Tell You (If You Ask the Right Way)

Let's start with the publishers, because this is where things get uncomfortable for every DSP running a premium CTV pitch.

We talked to Disney executives. Off the record. And to their credit, they were pretty honest about it: if someone is buying Disney inventory through open programmatic channels instead of going direct, those ads are not ending up on their prime shows.

Read that again. Disney is telling you that the programmatic path does not lead where the DSPs say it leads.

What actually leaks into the exchanges is remnant. We're talking back-catalog Hulu content. Filler placements. The kind of inventory that ends up playing on a screen in a doctor's office waiting room while you're trying not to make eye contact with the person across from you. Not the season finale of The Bear. Not Monday Night Football. Not whatever the DSP showed in the pitch meeting when they were trying to close the deal.

Disney sells Disney. What exchanges sell as "Disney" is a completely different product.

And why wouldn't that be the case? Think about it for two seconds. Disney has the most valuable ad-supported content library in streaming. Why on earth would they let that inventory get arbitraged through five middlemen at a fraction of the direct price? They wouldn't. They don't. They hold back the good stuff for direct sales and tightly controlled deals, because that is what any rational business would do.

So when your DSP shows you a campaign report that says "Disney+" or "Hulu" next to your impressions, what you need to understand is that the label in the bid stream can say anything. The question is whether the ad actually ran where the label says it ran. And according to both Disney and the people who measure this stuff for a living, the answer is: probably not.

The Only Six Places That Actually Matter

Both measurement executives, independently, made the same structural argument. Almost the same words. It goes like this:

Roughly five or six publishers account for about 95% of actual CTV consumer attention. This is not speculation. You can trace it through public filings, ad spend concentration data, and audience measurement. Consumer attention in streaming is violently consolidated.

The list: Disney and Hulu. YouTube. Amazon. Netflix's ad tier. Roku Sometimes. Maybe Peacock or Paramount+ depending on how you're counting. That's it. That's the entire universe of CTV that represents real humans watching real content on real screens.

Everything else in the open exchange, the long tail of a thousand-plus "publishers" that populate your DSP logs, is where the problem lives.

One source put it flatly: "Pretty much everything outside of six or seven direct paths is fraud."

Now, let me be straight with you about the numbers, because this is where the story requires some journalistic honesty. Both sources pegged the fraud rate on open-exchange CTV inventory at roughly 90%. That is an aggressive number. Independent benchmarks from verification and contextual vendors typically show fake or miscategorized CTV in the high single digits to about 20% on unprotected inventory. That's a meaningful gap.

But here's what matters: the published benchmarks measure the aggregate market. The sources are talking about open-exchange inventory outside the top publishers specifically. And when you zoom into that slice, the evidence starts looking a lot less comfortable. Documented fraud rings like CycloneBot have manufactured hundreds of millions of fake CTV ad requests per day, enough to swamp open-exchange supply for entire app categories during an incident. Experiments by researchers and measurement companies have shown that platforms will cheerfully accept, bid on, and transact obviously fake "CTV" traffic from devices that could not possibly be a television. We're talking about a smart fridge with a zero-by-zero pixel screen registering as a 50-inch living room TV. And the system processes it. And the money moves.

So is the overall CTV market literally 90% fraud? Probably not. Is the open-exchange CTV inventory that DSPs are selling you as "premium" overwhelmingly garbage? Both sources say yes. The documented evidence makes that very hard to argue with.

"Oh Yeah, This is Disney. No It F---ing Isn't."

Here's how it works, for those of you who have never looked under the hood of a CTV ad transaction.

Your DSP receives a bid request. The bid request says: CTV. Premium. Family entertainment. OEM device. Maybe it even says ESPN or Hulu or Disney+ right there in the metadata. Your buyer sees those labels and thinks, great, we're on Disney. The buyer is looking at a label. They are not looking at a living room.

Between the advertiser's dollar and the actual screen (if there even is an actual screen), there are multiple intermediaries. SSPs, exchanges, resellers, server-side ad insertion servers. At every single hop in that chain, there's an opportunity to misrepresent what the inventory actually is. And the incentives at every hop are to do exactly that, because premium labels command premium prices.

This is not theoretical. There are named, documented fraud operations that did exactly this at massive scale:

CycloneBot manufactured hundreds of millions of fake CTV ad requests per day by spoofing real apps and devices.

LeoTerra, CelloTerra, Monarch, and ParrotTerra used counterfeit server-side ad insertion servers to hijack SSAI sessions and mint enormous volumes of fraudulent CTV impressions across thousands of apps and IP addresses.

These aren't hypothetical attack vectors from a cybersecurity whitepaper. These are things that happened. That were documented. That involved real money from real advertisers who thought they were buying premium CTV.

The practical message from both sources is brutally simple: if you want actual Disney, you buy through Disney's own pipes or through very tight direct deals. If you're buying "Disney category" or "premium CTV" on the open exchange, you are buying a fundamentally different product that may have nothing to do with Disney, may not involve a real television, and may not involve a real human being.

The Inclusion List Problem

So the obvious question becomes: fine, if the open exchange is a sewer, just use an inclusion list. Only buy from the good publishers. Problem solved.

Not so fast.

In the course of reporting this, we found that Scope3 is building the inclusion lists for major agencies. Which immediately raises a question that should make you uncomfortable: if inclusion lists are the solution, who is building them, and what criteria are they using?

Because if the answer is "a third party whose business model depends on being needed," you've just recreated the exact same incentive problem that broke verification, one layer up in the stack. A company that sells inclusion-list services has a financial interest in the list being complicated enough to require their expertise, long enough to justify their fees, and updated frequently enough to keep the contract running.

The sources' position on this was almost comically simple. The inclusion list should be absurdly short. Six publishers. Direct paths only. If you need a vendor to manage a list of six names, the vendor is the problem.

What Comes Next

Here's what keeps me up about this story. It's not that CTV has a fraud problem. Everybody in ad tech knows that. It's that the fraud is structural, not incidental. It's not a bug that some clever criminals are exploiting at the edges. It's a feature of how the pipes are built, how the incentives are aligned, and how measurement is designed to obscure rather than reveal.

Both sources said the same thing, three weeks apart, without knowing about each other: the system is working exactly as it was built to work. It just wasn't built to work for advertisers.

In Part Two, we're going inside the pipes. How exchanges actually move CTV inventory. Why Dailymotion keeps showing up next to Disney in your DSP reports (and what that actually means). Why the fraud detection companies that are supposed to catch this stuff have a structural incentive not to. And why the only signal that actually tells you whether your ad ran in front of a human being is one that almost nobody is using.

The plumbing is the problem. And almost nobody wants to talk about it.

The Rabbi of ROAS

What You’re Missing

Everyone else prints charts.

While trade pubs recycle press releases, we explain how your “premium CTV” buy ends up on a screensaver, a bot farm, or an app that never existed.

Not theory.

Not vendor theater.

Actual plumbing. Actual incentives. Actual fraud.

Stuff you use in meetings.

Stuff that saves money.

Stuff people whisper about after hours.

Because ignorance is expensive.

Because dashboards lie.

Because someone in your org is already wasting 30% of your budget and calling it “scale.”

And because 400 of your competitors already read ADOTAT+ and would prefer you didn’t.

Subscribe to our premium content at ADOTAT+ to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

Upgrade