Sign up here |

|

|---|

If You Think You Understand The iSpot vs. EDO Case, You Don't

The Data Underneath

I met the iSpot case during a zoom call. Someone told us about the coverage like scripture, the kind of story you repeat at panels to signal you're paying attention. Clean verdict. Dollar amount that sounds like justice. Somethign Something Ed Norton. Two companies, one contract, lesson learned. Move on.

But I kept thinking about what wasn't there.

Not just one missing thing. The entire architecture of absence. Documents referenced but never shown. Legal findings buried in the eighth paragraph. Trade secret rejections mentioned once, then abandoned like they were embarrassing.

The way every outlet arrived at the same frame (theft, stolen data, unfair competition) using the same words, the same rhythm, like they'd all been given the same sheet music.

I don't know what actually happened between iSpot and EDO. I don't have time to wade through dockets and depositions, and honestly, I don't want to. I wish this lawsuit didn't exist. I wish none of these lawsuits existed. Measurement companies suing each other over who owns what slice of observable reality? It's not good for anyone. Not for the industry, not for the advertisers trying to figure out what works, not for the little companies watching the big ones define the rules through litigation instead of competition.

These lawsuits are expensive distractions masquerading as principles. They drain money that could build better products into lawyers' pockets. They create precedents that make it harder to innovate. They're the business equivalent of fighting over who owns the weather because you were the first one to write down that it rained.

But I know something happened in the coverage. Something that felt practiced. Rehearsed.

What Got Said

EDO's position, from what I could gather, wasn't "we did nothing." It was narrower: the ad airing is just a timestamp. What matters is what people do after.

Search lift. Engagement. The downstream. Outcomes.

You don't own the fact that something aired on TV. You own what you build on top of it.

If that's true (and I'm not saying it is, I'm saying the jury seemed to think maybe it was when they rejected the trade secret claims) then the entire measurement business rests on a premise nobody wants to examine too closely: that foundational data isn't proprietary. It's observable. Public. What you sell is the commentary, the layer, the prediction.

TV ad occurrence data isn't a secret. It's a compilation of things anyone with the right equipment could watch.

The jury agreed with that part.

That should've been the headline. It wasn't.

How Everyone Told The Same Story

I started collecting the coverage. Let me be clear: I hate this.

I really hate reading trade press. I hate reading most commentary in this industry. It's like watching someone chew the same piece of gum for three hours while explaining why it still has flavor.

Or maybe, if I am being kind, it's the complimentary breakfast pastries under heat lamps at the Marriott. Technically food. Technically free. Technically sustaining life. But mostly just there to fill time between panels about "The Future of Addressability."

But I had to know if I was imagining the sameness. So I did the thing I least wanted to do, which was open multiple tabs of industry coverage and read them like I was doing penance for past sins.

Deadline: "data was improperly obtained and then marketed to clients"

AdWeek: "scraping proprietary data... stole iSpot's trade secrets"

MediaPost: "improperly obtaining data from iSpot and then sold it"

It was like they'd all attended the same editorial prayer breakfast. Every outlet led with theft. Stolen data. Trade secrets. The same beats, the same rhythm, the same moral certainty.

I get it: iSpot has a great PR company, a great PR budget, which isn’t the point, but at the same time, is totally the point.

But buried in paragraph eight, sometimes paragraph twelve: the jury rejected the trade secret claims. Threw them out. Said the data didn't qualify.

So what was stolen?

The answer, it turns out, is narrower than the headlines wanted it to be: EDO violated the scope of a contract. They were licensed for "Movies." They accessed automotive, wireless, TV networks, insurance. They made millions of API calls pulling data they'd promised not to touch.

Breach of contract. Eighteen million dollars.

Not theft. Broken promises.

That's colder. Less satisfying. Doesn't give you someone to root for or against. Doesn't let you feel good about the system working, because the system is just contracts and lawyers, and the thing being protected isn't innovation or creativity, it's the right to be the only one selling analysis of TV commercials that everyone can already see.

Maybe that's why every outlet reached for the bigger story. The one with villains.

The Documents That Weren't There

AdExchanger did something different. They got closer to actual reporting. Woohoo.

"An internal email viewed by AdExchanger suggests EDO did intend to use iSpot's data to build a competing product. In a September 2017 message, sent by EDO CEO Kevin Krim to Norton, he mentions the company's intention to 'transition away from iSpot and steal their business.'"

Viewed by AdExchanger.

Not published. Not excerpted beyond that single phrase. Not contextualized. Not dated specifically within September 2017. Just viewed.

Then a second email: "We should access this API through some proxy to hide who we are."

Also viewed. Also not published.

Look, I get it. These emails are probably in court filings. They're probably real. But if you have a smoking gun, you show it. You publish the full text. You explain the context. You let readers evaluate it themselves.

Because "steal their business" could mean a lot of things. It could mean "violate our contract and commit fraud." It could mean "win their customers with a better product."

It could be trash talk between executives who say things in emails they wouldn't likely say in depositions. It could be what every VP says about every competitor in every strategy meeting ever held.

I don't know which. Neither do you. Because we can't see it in the coverage.

This is how evidence gets laundered. A court filing (which is an adversarial document, a persuasive argument, not established fact) becomes "documents viewed by AdExchanger," which becomes proof of intent, which becomes the frame for the entire story.

But if the email is as damning as that one phrase suggests, why not publish it? Why not let it speak?

Possible answers: Legal review. Source protection. Or maybe it's not as damning in full context.

Or maybe this is what trade journalism does now, offering the weight of evidence without the liability of showing it.

The Thing Nobody Wants To Say

iSpot's API didn't enforce the limits its contracts claimed to impose. Not an attorney, but that seems dumb.

EDO was licensed for "Movies." But they could pull automotive, wireless, TV networks, insurance, everything. Five million API calls. The system just let them.

This is security by policy, not by design. You put up a sign that says "don't go past this point" and then you leave the door unlocked and you log who walks through it and you sue them later.

Is that protection? Or is it a trap? Who knows? We don’t because the media refused to ask any questions, just cut and paste a press release from iSpot.

I don't know. Maybe both. It worked, in the sense that EDO now owes $18.3 million. Heh. But it failed in the sense that it exposed how absolutely fragile the whole thing is. How much of this industry runs on trust and vague contracts because building actual controls would cost money, slow things down, and force uncomfortable questions about who really owns what.

And now we've established, through expensive litigation that benefits no one except the lawyers, that the answer is: whoever has the better contract language.

Great. Wonderful. That'll really drive innovation.

What This Signals (And Why I'm Worried)

Look, I wish I had more time for this. I wish I could wade through every court filing, trace every email thread back to its source (ok, I probably will). But at some point I had to stop and make dinner. Two adopted kids and a fifteen-year-old who's already turned twenty-five need to eat, and they don't care about TV ad measurement litigation.

So this is what I can give you, in the time between work and dinner and trying to explain to a teenager why Edward Norton being in a lawsuit matters (it doesn't, except it does, except it really doesn't):

The coverage got it wrong. Not in the details, I haven't read all the filings, I probably never will. But in the frame. In what they chose to emphasize and what they chose to bury.

This case isn't about bad actors, no matter how much the media wants to create drama. It's about how the boundaries between licensed inputs and differentiated products are imaginary. Contractual, not technical. Enforced retroactively, not proactively.

It's about an industry built on assumptions (that courts would protect compilations, that "raw data" could be distinguished from "analytics") and now those assumptions are being tested one lawsuit at a time, at enormous expense, making everyone more cautious and the industry smaller.

And instead of reckoning with that, the coverage reached for something simpler. Emails with phrases like "steal their business" (which every VP says about every competitor).

Letters referenced but never shown.

Moral theater.

But these are the real questions: Why didn't iSpot's API just block EDO from accessing industries they weren't licensed for? Why doesn't trade secret law cover TV ad occurrence data? What does it mean that the jury said EDO broke promises but didn't steal?

I don't like these lawsuits. They make the industry smaller, more fearful. They turn competition into contract interpretation. They tell new companies: get lawyers before you get engineers.

But what I like even less is coverage that treats them as moral dramas when they're really showing us how little agreement exists about the basic rules of this business.

The industry deserves better. Better journalism. Better precedents. Better uses of eighteen million dollars.

But mostly, we deserve to stop pretending lawsuits like this are about protecting innovation when they're really about protecting market position.

Part II is coming. Who gets hurt next and why every analytics company should be terrified.

But first: dinner.

The Rabbi of ROAS

A Note on iSpot:

This is not an indictment of iSpot. I don't have time to sit and weigh through all the evidence, but here's what they told me through their representative: iSpot had little choice but to take action to defend their business and IP from blatant and repetitive breaches. A federal jury, after seeing and considering all evidence, ruled in their favor for a reason. The case number with the U.S. Court for the Central District of California in Los Angeles is LA CV 21-06815-MEMF-(MARx). Trial details should be available through the PACER court document system under that ID.

I have questions. I always have questions. But questioning the jury instructions on "raw data" isn't the same as questioning whether iSpot had legitimate grievances worth pursuing in court.

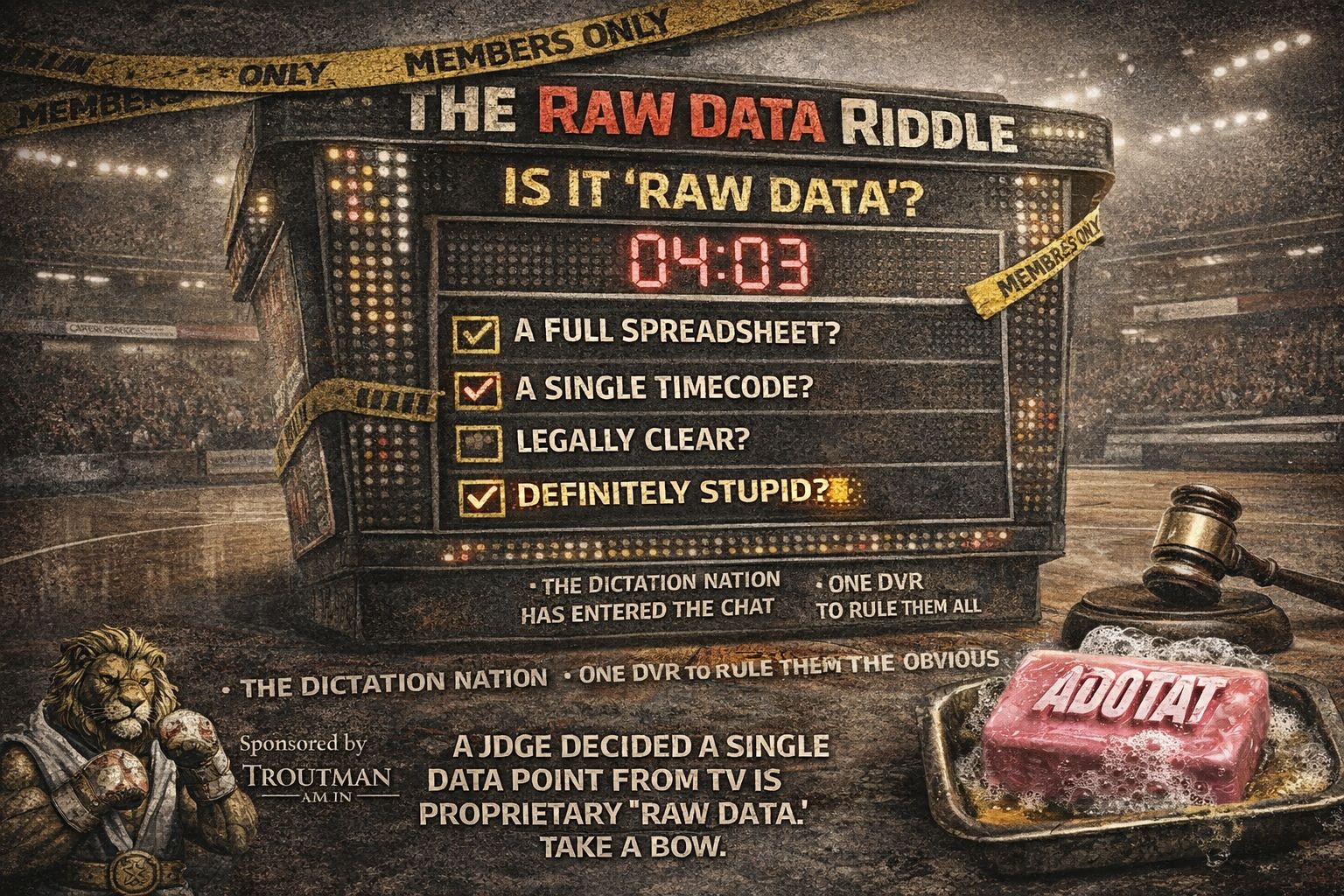

The Raw Data Riddle (Or: When Judges Define Technical Terms They Don't Understand)

I had to call an expert to understand this part. Not because I'm lazy. Because what the judge did in this case was so legally bizarre that I thought I was misreading the court documents.

Here's what happened:

In most contract disputes, the jury gets to interpret what disputed terms mean. They look at the evidence, hear from both sides, and decide: "Does this contract language mean X or Y?"

Not here. The judge defined "raw data" in the jury instructions. Just told them what it means. Case closed. No need to hear from people who actually work with data for a living.

What "raw data" actually means (according to Judy Shapiro, someone who actually runs a data company):

"Bulk, unprocessed datasets that can be independently reused or resold."

Think: massive CSV files. Database dumps. The kind of thing you can download, export, feed into your own systems, sell to someone else. Portable. Transferable. Standalone.

She distinguishes this from "standardized data"—individual fields like timestamps, network names, or creative IDs that are embedded inside an analytics product. You can see them, query them, use them within that platform, but you're not walking away with a transferable dataset.

She calls it "standardized" because making raw data useful requires work: normalizing formats, categorizing brands, structuring schemas, cleaning errors. That standardization process is where the actual value lives.

What the jury instructions said "raw data" means:

Any single piece of data qualifies as "raw data."

Any. Single. Piece.

By this logic, if you watch an episode of Grey's Anatomy, write down when a Chevy ad appears, and mention it to a colleague, congratulations. You've just handled "raw data."

Here's my source explaining why this is insane:

"You and I can just go watch tonight's basketball game, you can write down a timestamp of the ad that appears in the first commercial break, and in their words, that's 'raw data.' We're like, OK, that's ridiculous."

It is ridiculous. Because under her definition (the one that makes sense, the one the industry actually uses), a single timestamp isn't "raw data." It's a standardized data point embedded in an analytics context.

The difference matters:

If EDO downloaded bulk datasets they could resell independently, that's one thing.

If EDO queried iSpot's dashboard to see timestamps and network names while showing contextual analysis to studio clients (who already had their own iSpot licenses), that's using standardized data within the product as intended.

The judge's definition collapsed this distinction entirely. Made it impossible for the jury to understand the difference between "using a licensed service" and "extracting transferable datasets."

The result:

Eight jurors with zero background in media, advertising, or data licensing had to navigate this semantic quicksand using a definition that doesn't match how the industry actually works.

They landed on $18.3 million in damages, down from iSpot's requested $47 million. Nobody can explain the math. The number appears to have been plucked from the cosmic ether, which is what happens when you ask people to apply nonsensical definitions to complex technical disputes.

Bottom line: When judges define industry terms in ways that contradict actual industry practice, you get verdicts that satisfy no one and clarify nothing.

Appeals court, your table is ready.

Subscribe to our premium content at ADOTAT+ to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

Upgrade