Sign up here |

|

|---|

Pinterest, tvScientific, and the Performance TV Story Everyone Needs to Believe

The Lifeboat Theory

From the I Did Not See That One Coming Department came news that the ad tech startup tvScientific—a company built around the ambition of making TV advertising as easy to buy and measure as Instagram ads—was being acquired by Pinterest.

Mike Shields said what a lot of people in the industry were thinking, without trying to dress it up:

“What in the name of tasteful-yet-elegant decor is going on here?”

It wasn’t snark for effect. It was a genuine record scratch.

If the buyer had been The Trade Desk, which has spent years methodically pulling connected TV into its gravity well, or Comcast, which has openly tried to industrialize TV buying for smaller and mid-sized brands, the deal would have scanned instantly.

But Pinterest?

Pinterest is a large social platform and a serious advertising business, but it is also very clearly:

Not part of the Duopoly or Triopoly

Not on the buy side

Not a habitual acquirer of ad tech

And a virtual non-factor in TV advertising

So the question was never whether the deal was interesting.

The question was what problem this deal was actually solving.

Pinterest’s Longstanding Identity Problem

Pinterest has always lived in an uncomfortable middle ground. It is rich in intent and light on execution.

People go to Pinterest to plan. To dream. To assemble future versions of their lives. Travel itineraries. Kitchen remodels. Recipes. Wardrobes. It is, in theory, one of the most intent-dense environments on the internet.

And yet, Pinterest is rarely where transactions happen.

Fulfillment belongs to Amazon, Walmart, and Target. Retail media followed the checkout button. Pinterest followed the mood board. That distinction has always complicated attribution, even as Pinterest’s business has remained healthy.

Revenue is growing. Global MAUs sit around 600 million. Influencers are plentiful. But inside performance budget conversations, Pinterest often occupies an awkward position: appreciated, but not indispensable.

The friction appears later, when intent has to be translated into defensible outcomes. Attribution windows work against Pinterest. Conversion paths are longer. Incrementality arguments get harder once CFOs enter the room.

That gap—between inspiration and credit—is where tvScientific enters the story.

Why This Deal Exists at All

Pinterest’s acquisition of tvScientific has been framed publicly as a confident, forward-looking move into the future of performance television. The language is polished. The framing aspirational. The optimism carefully calibrated for investors who still want to believe acquisitions are driven by long-range vision rather than short-range pressure.

Kenneth Rona, PhD, Chief AI Officer at JWX, cuts straight through that framing.

As he put it:

“I don’t get the commercial logic, but I assume the people running Pinterest are not dumb.”

That sentence matters because it captures where many informed observers land: confused, skeptical, but not dismissive.

If you accept Rona’s premise—that Pinterest leadership knows what it’s doing—the transaction stops looking like a bold leap and starts looking like something narrower, quieter, and far more pragmatic.

This deal is not primarily about ambition.

It is about urgency, narrative continuity, and a set of stakeholders who all needed the same outcome at roughly the same moment.

Pinterest needed a performance extension it could credibly defend

tvScientific needed a buyer

Investors needed resolution

That convergence produced a deal that looks bold from the outside and feels deeply practical on the inside.

What the Deal Actually Is, Once You Remove the Ceremony

Pinterest has never operated a native, first-party CTV advertising business. That is not a footnote. It is the foundation of the entire transaction.

There was:

No internally built CTV buying stack waiting to be scaled

No proprietary TV-grade execution layer

No television-specific attribution system performance buyers could walk into a finance meeting and defend without caveats

Rona frames the decision cleanly as build versus buy, and in his view the answer was obvious.

“I’m thinking they got a bargain in terms of a build vs. buy decision and they were interested in having a more robust CTV product.”

This is not an expansion of an existing Pinterest capability. It is entry by acquisition, chosen because building this infrastructure organically would have taken too long and required too much proof at a moment when neither time nor patience was abundant.

Pinterest’s own language quietly concedes this. Executives repeatedly emphasize that this is the first time advertisers will be able to evaluate television with the same clarity they expect from Pinterest’s performance channels.

That phrasing admits the gap. It also confirms that the machinery delivering clarity is being acquired, not evolved.

Pinterest is not strengthening a muscle it already had. It is attaching one.

The Clock Was Ticking at tvScientific

According to an executive-level insider at WPP with direct visibility into the transaction, tvScientific was not casually exploring strategic options. It was shopping hard.

By late 2024, the company had spoken with roughly five potential acquirers in a matter of months. Internally, the cap table was described as “six months or bust.”

A 2024 financing round led by Idealab came with a 1x non-participating liquidation preference that escalated to 2x if the company raised again. Every additional month of burn without an exit worsened the economics.

At that point, the instruction to management was explicit. The CEO was told by investors to find a home for the company.

Pinterest was not the only interested party. But it was the only buyer willing to take out the entire cap table in cash. Other bidders wanted assets only, paired with 30–40 percent headcount cuts.

Once word circulated that tvScientific was under time pressure, leverage evaporated.

By diligence, the price was described as around $300 million, structured roughly as 90 percent cash and 10 percent restricted Pinterest stock, with no earn-outs. No earn-outs is not a sign of confidence. It is a sign that tvScientific had no negotiating power left.

Integration Is Not Optional

Internally, the decision came down to product, sales, data science, and finance, with a blunt overhang: if tvScientific’s CTV capability does not ship inside Performance+, the entire thesis collapses.

This is not a “let’s see how it goes” acquisition. It is a binary integration bet.

Fewer than half of the tvScientific team is expected to transition, with packages described as a mix of cash, Pinterest stock, and short-term consulting agreements.

The technology survives.

The org chart does not.

Separately from the public messaging, tvScientific × Pinterest has already begun rebuilding its sales leadership, starting with the hiring of a new Head of Sales / EVP Revenue Officer, slated to begin in mid-January.

This is not a backfill.

It is a reset.

The implication is straightforward: Pinterest values the capability, not the existing commercial motion.

Capability Is Not the Same Thing as Relevance

This is where Graeme Blake, CEO of Blutui, brings the argument to its sharpest point.

In Blake’s view, this deal does not reposition Pinterest. It is strategic only in the narrow sense of accelerating capability. It is not strategy in the sense of changing how the market thinks about Pinterest.

tvScientific, he argues, gives Pinterest “CTV performance grey matter quickly.” That matters. But it does not fix Pinterest’s deeper issue: Pinterest is still not where media plans begin.

Planners do not start with Pinterest. They do not anchor budgets there. Better tooling alone does not change that.

Blake describes the deal as feeling somewhat forced. tvScientific appears to have solid technology but a finite runway, which is not unusual. Pinterest gets the IP and the team it wants without taking on the entire company. That suggests this is about speeding up a roadmap, not making a big directional bet.

If Pinterest treats this as just another feature, Blake warns, it becomes more complexity and another thing sales teams have to explain.

Where the deal could matter is if Pinterest uses it to sharpen its positioning in the minds of planners and buyers. There is a credible story where Pinterest becomes a bridge between intent, inspiration, and TV scale.

But that is not a product decision.

It is an organizational decision.

Sales structure, packaging, positioning, and success metrics all have to change. Otherwise, nothing really moves.

And then there is the human reality. Integrating cultures—when one company is clearly the big spoon—amid layoffs and a very public acquisition is difficult. The partial team retention says a lot. This is about shipping and integrating, not cultural or commercial reinvention.

The Bottom Line

This deal does not make Pinterest a CTV powerhouse.

It does not give it inventory leverage.

It does not magically solve incrementality.

What it does is buy Pinterest time, a stronger attribution story, and a seat at the performance table it was at risk of losing.

For tvScientific, it is survival.

For investors, it is resolution.

For Pinterest, it is a flotation device.

Not a flag planting.

Not a moonshot.

Just enough oxygen to keep the story going.

Stay Bold, Stay Curious, and Know More than You Did Yesterday.

Jason Fairchild, in His Own Logic & Why Selling Was the Rational Outcome

Jason Fairchild didn’t frame the Pinterest deal as a leap of faith.

He framed it as arithmetic.

And if you track what he actually says, repeatedly, the conclusion shows up long before the press release.

“What If We Do for TV What We Did for Search?”

This is the line he keeps coming back to, almost unchanged:

“What if we do for TV what we did for search back in the day?”

He doesn’t say it as nostalgia. He says it as a design brief.

Search, in his telling, worked because it democratized access, enabled self-serve buying, and let marketers transact on outcomes instead of promises. tvScientific was built to port that exact logic into television.

But he’s also clear, implicitly, about what made search unbeatable.

Search sat on intent.

“You Can Create Intent on TV”

The Portland story is his proof, and he repeats it because it explains the entire company:

“You can create intent on TV.”

A $500 campaign.

A home-and-garden store.

800 website visits in 48 hours.

Lower cost per visitor than Google.

Search demand capped by reality.

Then the conclusion:

“It taught us a couple things. One, people do see an ad and respond. And two, you can create intent on TV.”

That sentence matters because of its precision. He doesn’t say TV captures intent. He doesn’t say TV replaces search. He says it creates intent, at scale, cheaply, and measurably.

That’s a powerful claim. It’s also a bounded one.

“People Watch TV With Their Phone in Their Hand”

Fairchild returns to this observation constantly:

“People watch TV, they have their phone or device in their hand 95 percent of the time.”

In his framing, this is the behavioral bridge that makes performance TV real. The TV ad triggers interest. The phone captures action. The household signal closes the loop.

He puts it plainly:

“They see something they’re interested in and either they’ll pause it or wait for the commercial, and then they’ll go do whatever it is they want to do.”

tvScientific lives in that handoff. It observes it. Prices it. Optimizes it.

What it doesn’t do is own where that curiosity ultimately settles.

“I Don’t Just Believe a Dashboard”

Fairchild is unusually blunt about trust:

“I don’t just believe a dashboard. I want to see the data at the log level.”

He repeats some version of this every time he talks about the platform. Radical transparency isn’t a nice-to-have. In his view, it’s the only way performance TV earns legitimacy.

He’s explicit about why:

“You can’t click on a TV ad. We’ve all been trained on last-click attribution.”

So tvScientific over-proves. Incrementality studies. Exposure-to-outcome paths. Household-level matching. No black boxes.

But listen carefully. Platforms that own the demand surface don’t have to work this hard to be believed. Transparency here is not moral positioning. It’s structural necessity.

“If We’re That Good at It, Let’s Just Guarantee the Outcome”

At one point, he describes a board conversation almost casually:

“If you’re this good at it, and you can tell the performance of an advertiser in the first few days, then let’s just guarantee the outcome.”

That’s confidence. It’s also a quiet admission that the optimization problem is largely solved.

Once the machine is that automated, the remaining upside doesn’t come from better math. It comes from owning more of the environment around the math.

Creative Intelligence, According to Him

When he talks about creative intelligence, he doesn’t romanticize it. He operationalizes it:

“If you introduce the brand name in the first six seconds, it’s a 25 percent increase in performance.”

He talks about regression models, tagging attributes, scoring ads, feeding that back into the next creative iteration.

In his telling, this isn’t about taste. It’s about making creative legible to performance buyers.

But again, he’s careful. tvScientific analyzes creative. It doesn’t host discovery. It doesn’t live where ideas are browsed, saved, or compared.

Why Pinterest Makes Sense, According to Him

Fairchild never describes the deal as emotional. He describes it as fit.

Pinterest already lives where people plan.

Where they browse before searching.

Where intent forms before it declares itself.

tvScientific proved, in his words, that TV can reliably move people from passive viewing to measurable action.

Put together, the logic is clean and, according to him, unavoidable.

He didn’t sell because tvScientific stopped working.

He sold because it worked up to a point, and he knew exactly where that point was.

In his version of the story, selling wasn’t giving up control. It was acknowledging where control actually resides.

And once you listen to what he’s been saying all along, the deal doesn’t feel dramatic.

It feels consistent.

🔥 ADOTAT+

Public takes on the Pinterest–tvScientific deal stop at mood. Relief. Fear. Integration. A few shiny reach numbers. That’s the polite version.

ADOTAT+ is where the real leverage shows up.

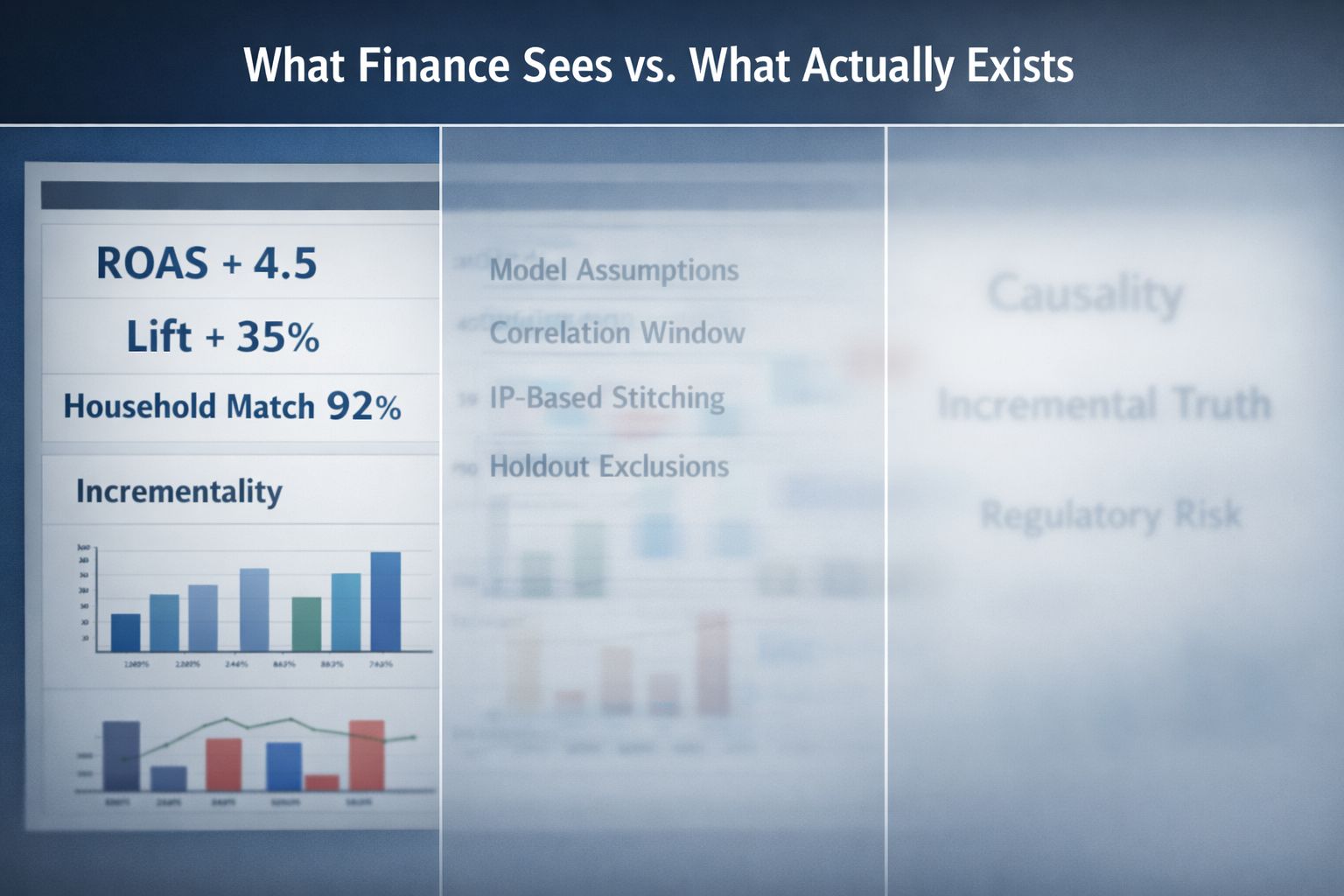

This deal is not about CTV scale or product ambition. It’s about who gets to define causality once tvScientific is wired into Performance+. Default attribution, even when imperfect, quietly beats perfect measurement every time. If Pinterest can ship a clean “Pinterest + CTV drove outcomes” story into finance dashboards, that narrative can redirect budget for multiple cycles before anyone dares to challenge it.

That’s the moat. Not inventory. Not UI.

Inside ADOTAT+, the focus shifts to what actually moves money: how attribution hardens into truth, why reach claims mainly buy entry into the meeting, where regulatory pressure starts to crack deterministic signals, and which of the three futures this acquisition is really optimized for.

This isn’t dominance.

It’s time-buying.

If you want the version without PR lighting and founder mythology, that’s behind the velvet rope.

Stay Bold, Stay Curious, and Know More than You Did Yesterday.

Subscribe to ADOTAT+ to read the rest.

Unlock the full ADOTAT+ experience—access exclusive content, hand-picked daily stats, expert insights, and private interviews that break it all down. This isn’t just a newsletter; it’s your edge in staying ahead.

Upgrade